Proposal Course: Session Two

Some thoughts on synopsis, pace and themes, followed by a guest post from Louise Kenward on developing a narrative.

Hi everyone,

This is the second post for my proposal course. You can find Session One here, and a link to the Zoom discussion on structure in the chat. Building on the first session, we’re going back to our structure and chapter outline to look at pace and themes while also drafting our synopsis.

These elements, which won’t be used beyond the proposal to pitch to agents and editors1, will be your roadmap to drafting the whole book. This stage is where you refine your ideas, link up themes, strengthen your arguments, do a bit more research and find your way through your narrative.

Synopsis

A synopsis is a concise summary of what you intend to cover in the book. It will work as an introduction for your proposal.

As you will be submitting sample chapters, that’s where we’ll get an idea of your writing style, so don’t worry too much about that here.

Your synopsis should be one to two pages long. You can find a bit more about the synopsis in my previous course:

In your synopsis, you may want to include:

Why you want to write this book

What qualifies you to do so (personal experience, interest or expertise)

Where the idea for the book came from

At the end of the synopsis, add how long you think the book will be and when you think you could deliver it (unless you have added this in your cover page):

Planned word count: Traditionally, non-fiction books tend to be between 60,000 words and 90,000 words (though there are always exceptions!). Anything less than that and it becomes a tough sell and anything longer is very costly to produce. (You will have seen longer non-fiction books on the shelves, but they will usually be by established authors or well-known people, big commercial topics, or books published pre-Covid.) Usually narrative non-fiction is between 60 and 80,000 words and more serious non-fiction (with bibliography and footnotes) closer to 70 to 90,000 words. Your planned word count can be approximate or a range: ‘approximately 75,000 words’ or ‘between 80,000 and 90,000 words’.

Planned full delivery date: As this is a proposal and not the complete book, it’s useful for agents and editors to know when you’ll be able to finish your book. Make this date realistic and achievable and give yourself an extra month or so as a safety net. While in some instances you can extend a deadline, it is better to pick a deadline that works for you. You can choose anything from six months in the future to one year or several. It is more customary for narrative non-fiction to have a shorter delivery than serious non-fiction featuring a lot of research, trips, experiments, surveys, interviews, etc. Bear in mind that the longer the period of time between now and your planned delivery date, the riskier it might feel to the publisher. They may feel that the book may no longer be relevant or stand out by the time it gets published, so try to bear this in mind when choosing your date.

Themes and Pace

Your synopsis as well as your work on the structure and the chapter outline will help you highlight your main themes and work on your pace. After all, even if your book is a non-fiction project, storytelling is a huge part of it.

Here were some of the topic we discussed during our Zoom about structure:

Setting of your book: we discussed the topic of when the ‘now’ of your book is — are you writing in the present tense and taking each moment as if to recreate your initial reaction? Or are you instead writing from hindsight at a point in the future? You don’t have to start your book (which is the retelling of something that happened) when the events start or end, you can choose a dynamic point in the story that sets you up. You can even set it halfway through your journey, or alternate timelines.

Taking a bird’s eye view of the book: By doing this work on structure, you will be able to take a broad view of your book and assess its themes. Are there any themes you feel you could turn the volume up a bit within the book and some where you could turn the volume down a bit? Are all themes threaded through each chapter or do they feel fragmented? Also, are you telling the story in the most engaging way? Are there other point of views, perspectives or even disciplines you could bring in that would make your writing shine?

Bring the reader by the hand: if your non-fiction book is specific and necessitates some knowledge (of facts, history, your life), then think about taking the reader by the hand — contextualise to help them understand where you are and why it matters to you. Some readers may know nothing about you or what you’re writing about, how can you bring them in to the narrative? I often find it helpful to frame this by asking my writers to tell me as if they’re telling an anecdote to a friend. Forget the jargon, the writing courses and the pretty writing, how would you tell someone this story? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces fall into place when you start doing that.

Writing around privacy: it’s difficult to write around privacy (we’ll discuss this in more detail in Session Four) but there are ways: you can anonymise, you can hint at things happening but not write about them in the book, you can bring in themes you’re talking about without using memoir.

Relatability: it’s always useful to think about relatability and how to make your specific experience or idea universal. For example, when I discuss

’s book The Ghost Lake, I refer to it as a book about all the things that used to exist but aren’t here anymore, and how much influence they have on the ones left behind. Or when I talk about Polly Atkin’s book Some of Us Just Fall, I emphasise that it’s a book about the stories we tell about our bodies. These are all universal experiences that are make the specific story shine.Pace: does all your action happen in the first half and the second half of your book has explanations? Or do you have two fact/history-heavy chapters at the start to ‘contextualise’ and then move on to a different type of writing? You may want to have a look at that.

Exercise:

Your exercise for this week is to go through your structure and chapter outline with these aspects in mind. Do join the chat if you have any questions!

GUEST POST:

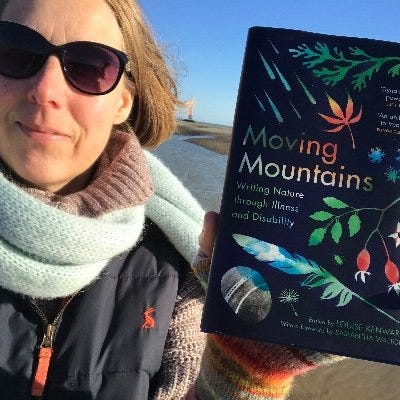

Developing a narrative by Louise Kenward

There’s something different, I think, between writing a book when you set out to write a book, and writing a book based on something you did and then thought, ‘this would make a great book’.

I have spent ten years trying to do the latter. While Moving Mountains: Writing Nature Through Illness and Disability is the most recent book out in the world with my name on the front (and was comparatively straight-forward to structure), I have been working on my own full-length manuscripts too. A Trail of Breadcrumbs began many years before Moving Mountains was conceived. Perhaps it’s just writing your first book that makes it so difficult. Starting to write my second full-length book, with my PhD (Inhabiting Instability), it feels clearer how to structure the work, because I’ve done it once and I learn by doing, but also because I can see the difference between starting a project that will be a book and finishing a project that I’m trying to make into a book (I withhold the right to change my mind when I come to finalise this second book).

Writing Inhabiting Instability, I have an idea of the themes I want to explore and am making work that relates to these themes. I am (crucially) discarding anything that isn’t relevant. The process is still circular: researching, writing, editing, researching, writing, editing – but I am travelling in narrower circles than I have done with A Trail of Breadcrumbs.

Breadcrumbs started with an overland journey round the world. It started with getting sick two years before I left the UK. It started with encountering a Victorian woman’s museum collection in my hometown. All these things, and more, are true. At what point do I start? With my childhood wanderlust? My broken marriage that left me living alone without any other responsibilities? Losing my job? I have so many inciting incidents it has been tricky knowing where (and when) to start. Everything leads to everything else, and because it is my life, it is all woven into itself. It is difficult to lay it all out as separate threads, it is difficult to disentangle the work (and the material) from each other (from me).

After returning from my travels, I joined a writing course to learn how to write the book. While I was given advice about how I needed to include all the reasons for my journey, trying to do this became an almost impossible task. Trying to create the narrative arcs that were expected of my book squashed the energy of the book and my interest in it, I couldn’t fit the story to the map I was given. I have had to draw my own map. I suspect this is the case for many books. I think this is the synopsis.

Being able to distance myself from my own story has been difficult, I’m continuing to live it. The story became so complex, with so much material, all of it bunching up and wandering into new rabbit holes, it has been difficult to know what to include and what to edit out.

It has been helpful to have time to myself with the book, time away from the book, and time with someone else (a trusted, knowledgeable other) at different points in the process. I finally have some core threads to pull at, themes that are (I hope) relatable for the reader and are embedded in the text, things I hadn’t necessarily seen – because they were perhaps, so obvious (to me).

Time to myself with the book: this has helped me to be honest about what the journey was like, to write without a reader, what it meant to me and brought for me, what I experienced and what I didn’t. Above all, this was not a ‘recovery journey’, which had been an internal and implicit pressure – and if it wasn’t a ‘recovery journey’ what was it? This was, perhaps, the first (series of) drafts.

Time away from the book: that necessary distance to not think about it and do other things, to read widely and to write about and talk about something different. It’s exhausting going around in circles, writing and rewriting the same thing from different perspectives, trying to find the perfect complete picture. It is hard to see what is working. Time away separates you from the work. I needed to see it as a project – to make it a book, and not a journey I took, or a period of time in my life. This helps to lessen the entanglement and enmeshment of the writer with the writing. It helps to clarify what content is needed to illustrate the themes and narrative threads that you choose for your book.

This is also a time when it’s been helpful for me to read other people’s work. I hadn’t a clear idea where my book fitted, I hadn’t found anyone whose work resonated with my own. I needed to read to know what already existed, as well as what did not.

Time with (trusted, knowledgeable) others: talking about and returning to the book, now with less personal involvement. It was helpful to find a way into the project that untangled my own ideas and commitment to it and saw it as something separate to me. This may not only be the case in memoir, as writers we are often involved in our work at a personal and all-consuming level, but memoir is so much more personal it may be all the harder to draw the distinction from the writer to the writing. The writing shifts from being something I have done to something I’m making for a reader – it changes from being my life, to being a version of my life.

Crucially, I had so much material I could have written several different books from the single journey I made. I had attempted to include them all and it became unwieldy. I attempted to simplify it by taking out crucial parts and the book didn’t make any sense. When I tried to introduce them back in, there was so much material I couldn’t fit it all in. I couldn’t see what was important and what needed to stay for the story to be coherent, and what was important to me (as the person who lived through it) but didn’t need to be told for the story to hold true. I couldn’t decide what I wanted to say. I needed to make decisions about what story I wanted to tell – or what story my journey best illustrated. I also needed the clarity of a second person (Caro) to see what was necessary for it to make sense and hold.

The narrative threads of the book have informed the themes – these are the crucial elements that, being the person living through these experiences, haven’t always been easy to see. They’re the scaffolding of the book, over which the story is laid. They might be difficult to pinpoint, underpinning the assumptions and beliefs you come to writing the book with might be difficult to see or articulate. It’s helpful to have distance, space, and time, from the work to be able to see what it is I’ve been wanting to say. What’s the most important aspect? I’ve needed to have the space and time to process what happened to me to be able to write what needs to be written, and then to consider what feels important (and safe) to include in the book. The themes and narrative threads are the reasons the reader picks up and reads the book, they need to be clear and carried throughout.

It has felt like turning the book inside out, unravelling it all and laying out the meaning rather than the sentences – unpicking the intention and then piecing it back together with this at the forefront of my mind. It’s helpful to remember that readers will know nothing about me or my journey other than what I tell them. I cannot make assumptions of the reader beyond that. They cannot see into my mind or my past. I must tell them everything they need to know to make sense of the work.

The synopsis is the process of condensing the prose and focusing on these elements – how are the themes carried through the story? What are the events and experiences that illustrate these themes best? If the book is still a work in progress, the synopsis illustrates how the book will develop, it gives the structure to work to when continuing to write. It’s the map you are writing for the publisher/agent, and for yourself, to find your way back in, helping you stay on track.

Choosing the themes is about decision making. The book needs then to follow these, knitting everything back into this pattern, picking up loose threads and stitching them into place. While you might learn more about the themes through the process of writing, the time spent discussing and reflecting can help to see what comes through, to be able to then write with that intention.

Louise Kenward is a writer, artist and psychologist. Her writing has featured in Women on Nature, The Polyphony, The Clearing and Radio 3 (Landscapes of Recovery). In 2020, she set up ZebraPsych with the aim of raising awareness of energy limiting chronic illness, and she co-produced the anthology Disturbing the Body (Boudicca). Louise was Writer in Residence with Sussex Wildlife Trust (2021-2022) and is a postgraduate researcher at the Centre for Place Writing, Manchester Metropolitan University.

She is the editor of Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability, a first-of-its-kind anthology of nature writing by authors living with chronic illness and physical disability and on Substack.

Thank you so much

for sharing your experience on developing a narrative! I can’t wait for you all to discover A Trail of Breadcrumbs!I hope that's all clear, and not too intimidating. Let me know in the comments if you have any questions — there are no silly questions. Publishing can be opaque at the best of times, so if there's anything I can do to make it more transparent, I'm happy to help!

Coming up next week is a post on biography, market and readership and a guest post by the brilliant

!Until next time, keep on writing!

Caro

Really, really frustrating I know, but super useful to do, I promise!

I found @lousiekenward's words here super super comforting! I've been writing a very personal narrative for 5 years now, and have been through a very similar process to what Louise describes here. It's only now that I'm at the point, with time alone, time away and time with trusted others that what, precisely the real kernel of the book is and now I really really have that, the structure and pacing and everything else is so much easier to sculpt.